NORTH BATTLEFORD — Questions running the gamut from "Do you count your steps?" to 'Is your dog blind?" have been posed to Michael Huckabay by people curious about how he gets around.

Huckabay is a 25-year-old resident of North Battleford who moved here with his parents two years ago. He enjoys reading, making and listening to music, sports and computers. He hopes to one day find employment in the information technology world despite a significant visual impairment. He just needs the right position and the right employer to give him the opportunity, he says.

His dream job, he says, would be to work for Apple in some capacity; he presently has two Macs and an iPhone, and uses the voice over feature to tell him what's on the screen. Although he has stocked shelves and cashiered, webpage and blog creation plus the work he did at a Christian radio station in Ontario - including creating, writing and recording short segments for the air - is what truly inspires him.

Born with retinitus pigmentosa, Huckabay's vision is limited to being able to distinguish between light and dark.

"I can tell when I'm in a sunny room or if the light is on," he says.

He's never been able to see colour, but until he was about 16, he could read extra large type and distinguish some shapes. Retinitis pigmentosa causes a slow but progressive loss of vision due to the gradual destruction of some of the light-sensing cells in the retina.

It's interesting to note that Huckabay uses the words "see" and "saw" as well as "watch" and "watched" in the same context as a sighted person. It refers to his experience of something, like "watching" a television show by listening to the dialogue, announcer or, when it's available, the descriptive video. "Reading" is listening to audio books or using braille. Although he wears hearing aids after a virus affected his hearing about 10 years ago, he prefers audio books over braille, mostly because braille books are large and cumbersome.

While braille, audio books and alternate technology such as audio GPS applications have been developed for the visually impaired, there is another, more animate tool available to individuals such as Huckabay. That is developing a "working" relationship with an animal.

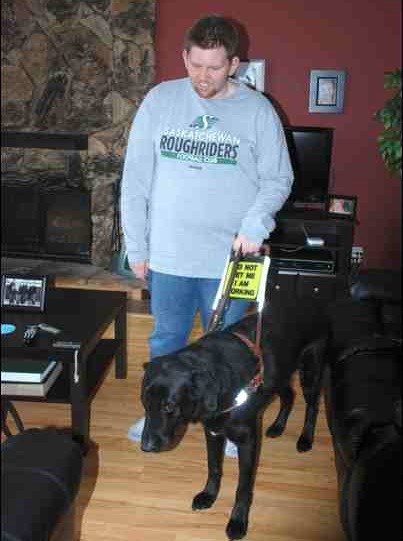

Kersey, a trained leader dog, is Huckabay's companion and assistant. The black shepherd-labrador cross came into Huckabay's life through an organization that provides guide dogs to people who are blind and visually impaired to enhance their mobility, independence and quality of life.

Four years ago, Huckabay travelled from his then home in Dryden, Ont. to the Leader Dogs for the Blind campus in Rochester Hills, Mich. for a 26-day course on working a guide dog in country, city and nighttime travel, on how to incorporate a guide dog into a daily routine and on dog care knowledge.

Kersey, says Huckabay, was chosen for him based on size, stamina and travel pace. At 70 pounds, Kersey is a big dog compared to some assigned to others in his leader dog class or to his schoolmates.

"Some of my friends are pretty tiny," he says. "Their dogs are maybe 40 or 50 pounds."

Huckabay lives with his parents Al and Judy Huckabay. His father is the senior pastor at Living Faith Chapel Apostolic Church and his mother is a facilitator with its Bridges for Children program. Although he has hopes someday to live on his own, he enjoys residing with his mom and dad.

"I think the older you get you appreciate them differently."

Huckabay went to school at W. Ross Macdonald School in Brantford, Ont., a school for students who are visually impaired, blind and deafblind. For eight years, he did a weekly commute from Dryden, where his father was pastor with the Full Gospel Church, flying every Sunday to Toronto, then travelling by vehicle to Brantford. Friday, it was the reverse. During the week, he lived on campus. He was involved in the senior choir, the yearbook committee and the student council. He was also a member of the wrestling, swim and goal ball teams (goal ball is played with a ball that has a bell attached).

Some of his friends at school had leader dogs.

"I saw others who had them and saw what they can do."

They had been to the Michigan guide dog school, so that's where Huckabay went, too.

The school has its own kennel and breeding program, says Huckabay. Once the puppies are about six weeks old, volunteer "puppy raisers" take the dogs home to housetrain them and teach them manners, practise basic obedience commands and socialize the dogs through exposure to different kinds of people, environments and animals in preparation for their lives as guide dogs.

What most people don't realize about guide dogs is that they are working dogs, says Huckabay. They shouldn't be treated like pets. For example, says Huckabay, one should never pet a guide dog when it's working. It may become distracted, jeopardizing the safety of its handler.

"You shouldn't even make eye contact," he says.

Kersey spends nearly all his time with Huckabay, even when he's not working.

"When we first came home [from the leader dog course] no one else could pet him or be around him because they want the dog to bond with the owner."

They sleep in the same bedroom and, even out of harness while in the house where Huckabay doesn't require his help, Kersey is usually in the same room.

When Huckabay goes out, Kersey is usually with him. (Huckabay also has a GPS audio app on his phone.)

There isn't really any place a guide dog isn't allowed, says Huckabay. He carries a card indicating Kersey's status as a guide dog, but there are some places it's better not to take him. Hockey games, for example. Kersey doesn't like the noise.

"He just howls, actually."

There are times when a handler is better off with just a cane, such as learning a new route or area.

"Sometimes it's better to learn an area first without the dog," says Huckabay.

"The perception is that you can tell a dog, 'take me here' and he'll take you there, you can tell him 'go to the grocery store' and he'll take you there. It doesn't quite work that way," he says. "You have to know where you want to go. The dog just helps you get to where you are going."

Winter, however, can make the going tough.

"Winter isn't very good for them because they are taught to stop at curbs, then you take your foot and slide it forward to find the edge of a curb."

In the winter the curbs are obscured by snow.

"I don't think there's a blind person that doesn't hate winter sometimes, because it's so hard to travel."

The dogs are also trained to go around obstacles, such as a car sticking out of a driveway halfway across the sidewalk, he says, and if they can't go around, they are trained to stop.

Huckabay says there's a story about a handler working his dog one day when it stopped. He gave the command for it to go forward, but it still wouldn't go. So he signalled with the harness for the dog to proceed.

"Finally the dog went forward and he and the dog went into a lake because the dog was trying to tell him he was at the end of a dock," says Huckabay. "Probably the biggest thing is just learning to trust your dog. That's probably the part that takes the longest."

Huckabay adds the dogs are also trained to avoid moving vehicles, and he knows well why.

"Not long after I got home, I was out walking with Kersey. We came to an intersection, I had stopped, I told Kersey to go forward and I started crossing."

A car appeared and the driver didn't seem to see them. Kersey wouldn't let him go forward, and as the car passed by, he crossed his body in front of Huckabay.

"Their training teaches them to stop and to protect their handler."

He's heard stories about dogs actually pulling their handlers backward out of such a situation.

Huckabay says it's not usually necessary to use a leader dog indoors, especially around the house.

He says people ask him if he counts steps to find his way around. He says, "It's a little difficult to do it that way. Usually what you do is explore and map it out in your head. Sometimes I'll get someone to come with me in a building and tell me what's in it and where different things are first."

Huckabay is used to answering questions about his life with Kersey. He has visited the daycare his sister's daughter attends in Dryden and done classroom visits here and in Ontario.

One thing enquiring young minds seem eager to know is how he can tell when Kersey is going to the bathroom.

"Some people ask me how do I know when he's going," he says.

Kersey may circle around a bit before he settles into a position to relieve himself, then Huckabay runs his hand down the dog's back to his tail, which indicates which kind of bathroom break he's taking. It will either stick up or straight back. If it's the latter, Huckabay puts his foot up next to Kersey's backside to mark the spot and gets a scooper bag ready. When Kersey moves away, Huckabay reaches down beside his foot, with the bag over his hand like a glove, and picks up the result for disposal.

Another question Huckabay gets asked makes him chuckle.

"I've actually had people ask me, 'Is your dog blind?' and I say, 'Well, it would not be very useful if I was blind and the dog was blind.'"

(Huckabay doesn't mind the term blind although he says it is "kind of harsh" and some people take offence to the term blind.)

He's even had people ask him how he eats, explaining he can ask someone to tell him where things are on the plate are according to the hands of a clock. Getting the fork to the mouth is no different for him than sighted people.

"Even people who have sight sometimes have problems hitting their mouth," he jokes.

He also does some cooking. He can tell when things are done by a combination of timing and smell.

"I'd have to say the slow cooker is a very useful thing, you can pretty much do anything with it."

Kids have also asked him how he gets dressed without seeing different colours.

"I don't have a lot of random colours," he says. "Most of them go together."

He laughs, "Some colours I'm glad I don't have to see. People tell me what they look like and I think, whoa! like hot pink!"

Although he can't see them, he likes to say his room is painted in Edmonton Eskimo colours. He's a sports fan. Including the Roughriders.

"They did pretty good last year," he says. "Not sure how well they'll do this year with all the players they're losing."

He also likes the Battlefords North Stars, Edmonton Oilers and L.A. Kings.

"I'm also a big Nascar fan."

His musical interests run to bass guitar and percussion. He enjoys his djembe, a goblet shaped drum of African origin played with the hands. He has taken part in musical worship teams here and in Ontario through his family's church.

He is enjoying his new home community.

"I find it very friendly," he says.

And he has no problems about sharing how his life is different than others.

"I have to say if everybody was the same it would be a pretty boring world," he says. "And most people like a good story."

.png;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)