As the First World War ended in 1918, one third of the men who enlisted from Bresaylor were killed in action. The returning Canadian soldiers brought back the Spanish flu.

Bresaylor School opened in the fall, though many of the larger schools, such as the Paynton School, located eight miles to the west, didn’t open that fall. After a couple of months, the majority of the Bresaylor school children became ill with the measles, then before recovering, many families became sick with the Spanish flu. All the students and the teacher became ill and the school was closed.

One Sunday it was reported in the hamlet that not one child was well enough to go outside. Many adults contracted the disease and had to stop work and recover. From reading family histories, at least three adults in the Bresaylor area died from the Spanish flu, possibly more.

Worldwide, the first wave of the flu epidemic spread across the globe in the spring and summer of 1918, but the second wave in the fall proved more deadly. The Spanish flu took 5,000 lives in Saskatchewan, 50,000 lives in Canada and around 20 million lives worldwide. It claimed more lives in two years than the war had taken in five years. Only 17 million lives had been lost in the war.

The first public mention of the disease in Saskatchewan was in The Regina Leader on Oct. 1, 1918. The disease continued to spread over the next three months with the peak number of deaths in November. Many deaths occurred within 24 hours of contracting the disease, though most died around the 10th day. The flu affected individuals between the ages of 20 and 40 more severely, leaving many children orphans.

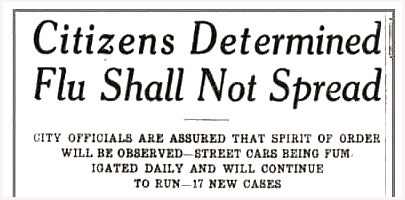

Schools, theatres and public buildings were closed to try to stop the spread of the flu, and people were discouraged from holding public meetings and attending public events. Additional cleaning and disinfecting measures were taken at public places. Streetcars in cities were fumigated and sprayed with formaldehyde nightly. Hotels and schools were converted to makeshift hospitals for overflow patients. Those who had any medical training were urged to assist.

Â鶹´«Ã½s reported the number of cases daily and urged people to remain calm, follow public health guidelines. Cleanliness, personal hygiene and not coughing in public were also recommended. Those who were sick were quarantined.

Ever wonder why in the old days post offices and ticket offices were closed in with only a small opening through which to conduct business? It was perhaps for the protection of employees from catching dreaded diseases.

After the pandemic, some changes were made in health care. As an incentive for doctors to remain in the rural areas, rural municipalities started paying doctors from taxes collected instead of having them make a living solely off direct billing. Building rural hospitals became a priority and vaccines gained popularity. Courses on the medical care of children were instituted for women in rural areas.

Thus ended a tough time in local and world history.

Check out the Bresaylor Heritage Museum Facebook page for more information. The museum is open by appointment only from June 9 to August 31. Please phone 306-895-4813.

Following is an account by a visitor to the museum at a recent volunteer activity.

Artefacts

By Donna Finch

I am driving west from Battleford on the Yellowhead Highway on what is expected to be one of the hottest days in recorded history for the area. Grey smoke from the wildfires burning only a couple of hours north just past Meadow Lake block out the big blue Saskatchewan sky I was looking forward to seeing. Home for me is Mount Forest, Ont., about a 30-hour drive southeast if you take the shortcut through the United States – but we are still in the pandemic and so cannot cross the border and, anyway, I flew Toronto to Saskatoon this trip since there was not enough time to drive. A Facebook post from the Bresaylor Heritage Museum from only a few days earlier that read “Artefact Photography Day – Volunteers Needed” is what has brought me here for my third visit to Bresaylor, Sask.

It was four years earlier, in 2017 while poking around online that I stumbled upon a post by my cousin and aunt asking for information on a man named Henry Sayers, a place called Bresaylor and the name of my great-grandmother Jemima Sayers. This was the first time I had any information about my maternal side of the family and so taking these three pieces of data, I began my research. A whole new world slowly unfolded for me beginning with the Bresaylor Settlement, and back to Red River, and before that the beginnings of the Hudson Bay and North-West Companies in what is today called Canada. Neither my grandmother nor my mother ever spoke of from where or who they came. Both are gone now. Did they know any of this rich history? Did they feel the need to hide this? How I wish I could ask those questions and share this with them. My grandmother was indigenous in appearance and as a child I asked my mother what kind of Indian is grandma? She answered Cree, and that was as much as she would say. I know now that she was Métis. Why did mother say Cree? Another unanswered question until I learned that my mother and grandmother spoke Cree - and so that is how she described them.

I grew up in a city three hours away from grandmother where I benefited from all the white settler privilege and absorbed all the baked in biases of the Ontario educational system of the 1960s and70s. I was proud to come from grandmother, but that was easy to say when I never experienced any of the racism that comes with it. In these days of Truth and Reconciliation I struggle to reconcile the two sides of my ancestors - my paternal ancestors left Europe for what is now called New Jersey and Â鶹´«Ã½icut in the 1600s. Many fought as United Empire Loyalists in the American Revolution and after losing the war, came to eastern Canada and eventually Ontario. They were colonizers on both sides of the border.

Today I can proudly share with my grandchildren the names and places out of which they come with less fear of repercussions than my grandmother could. Roots that extend into the beginnings of the fur trade more than three hundred years ago. That is when the Cree and Dene and Ojibwe people already here on Turtle Island welcomed the men arriving from England and the Ornkey Islands of Scotland as well as other parts of Europe. The coming together of these peoples and their distinct cultures was the genesis of the Metis Nation. I don’t believe my mother or grandmother knew we came from people like John Thomas Sayers and Bwanequay Obemau Unoqua at Fond du Lac, Peter Fidler and Mary Mackagonne at York Factory, William Rowland and Betsy Ballendine at Carlton House, John Alexander Isbister and Fanny Sinclair at Oxford House, or Alexander Bremner and Betsy Twatt at Red River.

As I arrive at the Bresaylor Heritage Museum I find several pickup trucks and cars parked on the grass beside the small lane running up to the buildings. A white tent has been erected between the two main buildings that face one another – a two storey white clapboard house with green trim which is the museum and the single-story house of the same style that is used as an office. Just a few yards the other side of the buildings and tent and separated by only a grassy ditch, the highway traffic thunders by – the Yellowhead was run straight through where the original hamlet of Bresaylor stood many years ago. I spot Velma Foster, a familiar face and stop to say hello. She is a tall sturdy octogenarian, fiercely independent, talented print artist, chief compiler of the “Bresaylor Between” history book, and curator of the museum for over 40 years since returning back to the area in the 1970’s. It is her dedication to the Bresaylor families and the museum that makes it possible for us to gather in this place for the next three days. We speak for a few minutes, and she introduces me to the others in the group.

Ironically, the severe heat that threatened to cancel the event is tempered by the sunscreen of smoke from the wildfires also caused by the severe heat and drought conditions. The pandemic protocols have recently been lifted in Saskatchewan and so each person forgoes the masking and social distancing rules we have all been forced to live with for the past sixteen months. I feel a little guilty as I think of my friends and family in Ontario where you still can’t even eat inside a restaurant or get your hair cut. I suspect, like myself, that most if not all of the volunteers are double vaccinated – especially the older. Most of the group are my cousins, first, second, third, fourth, fifth, even sixth, and once, twice, or three times removed. We carry the DNA of the founding families of the Bresaylor settlement. I can hear the echo of the ancestors in their voices as they laugh and share stories and in their resolve to preserve the unique history. Although this is my first time meeting these people and despite my introverted nature, I experience a sense of familiarity and ease. I had not known what to expect and had almost cancelled my plans several times – was I crazy to fly from Ontario, rent a car, book a hotel, in the middle of a pandemic, and a heat warning, and wildfires?

Carefully, for three days, we don white gloves and carry the artifacts one by one out of the museum to the tent. Then each is logged with an identification number, professionally photographed for a future website and virtual museum, measured, catalogued and returned to the museum. Kitchenware, clothing, farm tools, personal items like eyeglasses and brooches, needlework pillows, a buffalo skull, a saddle, leg irons, a fragile book of meeting minutes for the school, and a huge sickle are just a few. Each day there are around twenty volunteers participating. Velma is a constant, watching, listening, sharing her knowledge of the artifacts, how they came to be here to whom they may have belonged. My favourite piece is a black pot purchased in 1870 in Red River and brought to Bresaylor by Henry Sayers in 1881 – it provides a link to the time before Bresaylor at Red River, the place from where they all came – and possibly and most importantly for me, to Henry’s first wife Mary Bremner, who died in 1881 and is buried at Headingly, Red River. I always think of Mary and how she was left behind as her husband, brothers, children, and mother headed west to establish this new settlement. Did Mary use that pot, lift it from the stove or fire, fill it with water, wash it? We can only assume that she did.

Each day we break for lunch and sit in the cool shade under the trees behind the office – except for the third day when the sweaters and jackets make an appearance after a change in the weather. The food is homemade and delivered by three lovely women, Marion McDougall, Margaret Currie and Margaret Webb. We enjoyed sandwiches, chili, salads and deserts and even homemade bread. On the third day we had the most delicious pizza and fresh salad from Maidstone courtesy of Nutrien. By the time we wrapped up on Sunday more than 200 artifacts had been processed by the volunteers.

On the flight home I feel grateful for having been able to take part. I feel the energy of the ancestors, sparked by this coming together and the speaking of their names and respectful handling of their possessions in honour of their memory. It is their strength that lives on in us today and will continue in those who are yet to come.