Dear Editor

It is difficult to express the horror and grief many people across Canada felt this week after the Tk'emlups te Secwépemc First Nation announced that 215 Indigenous children were found buried on the grounds of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School which operated from 1890 to 1969.

Here in the Battlefords, across Saskatchewan, and throughout Canada, residential schools and colonialism are part of our society’s architecture. Non-Indigenous people, myself included, need to do our own work to understand this history, its context, and how it connects to what Indigenous people and communities experience today. For non-Indigenous people, the stories of those who experienced abuse or died in these schools can be viewed “from the outside looking in.” For Indigenous members of our community, these stories are personal and painful reminders about violence and cruelty, directly or intergenerationally inflicted on them and their family members. They are traumatic lived experiences that cannot similarly be viewed through a pane of glass.

Indigenous Elders, Indigenous young people and students, and Indigenous leaders should be listened to and their words should be shared. We owe gratitude to Indigenous community members who have taken time through past decades and today to do the difficult, emotionally taxing work of sharing knowledge about the real history and culture of this area - a history not always taught in museums and history books.

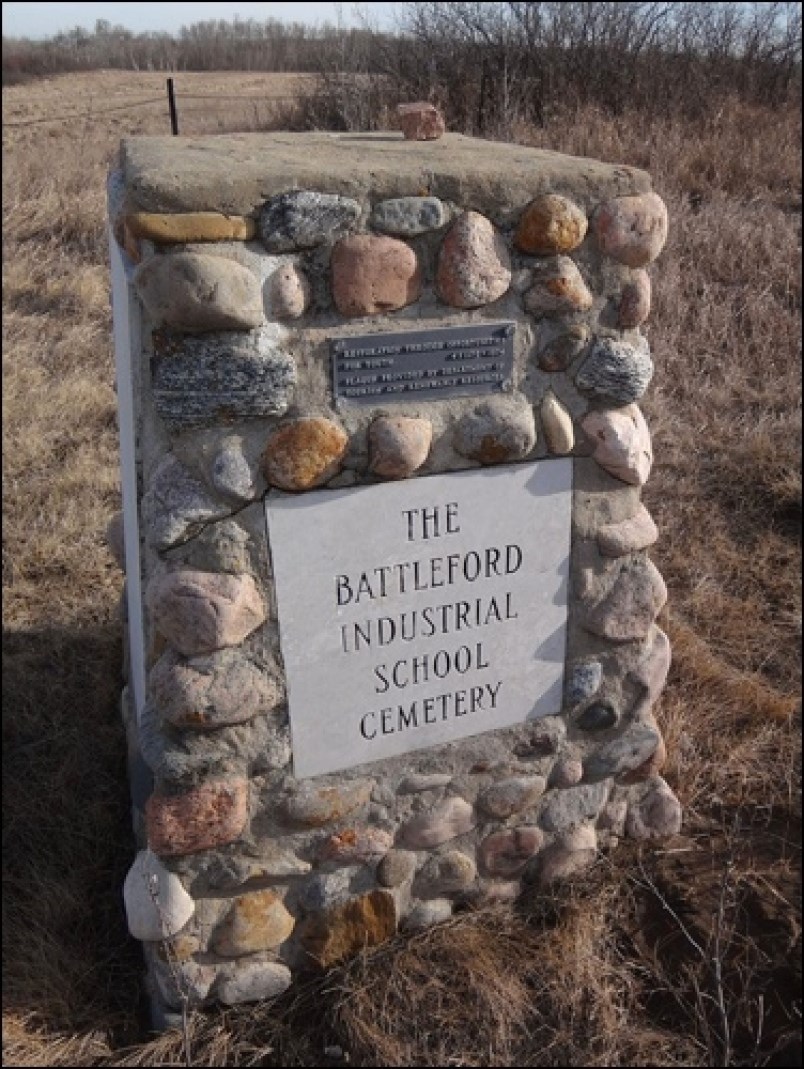

This week, during a community walk to the Battleford Industrial School Cemetery organized by Mosquito, Grizzly Bear’s Head, and Lean Man First Nation, Chief Aguilar-Antiman reminded attendees that although Battleford Industrial School closed in 1914, a number of Saskatchewan residential schools remained operational until the mid-1990s. This is not ancient history - it is part of our current reality. Numerous local people and groups have called for a better understanding of the Battleford Industrial School, its cemetery, and the many children buried here. Careful documentary research shows many more children died at the Battleford school than those identified in official records.

In a place with our history, where Indigenous members of our community experienced the Riel resistance, the imposition of Residential and Day Schools, the Sixties’ Scoop, and more recently the tragedy of Colten Boushie’s killing and the racism in Saskatchewan brought into sharp and painful focus over the past few years, it remains imperative that we consider where we might be able to make change in our community, implementing the Calls to Action published six years ago by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Here are three examples.

A few kilometres away from the Battleford Industrial School Cemetery is the gravesite of eight Indigenous warriors executed by the federal government and Northwest Mounted Police in 1885 to send a message to local Indigenous people about who was in charge. This was the largest mass execution that ever occurred in Canada. Like the Battleford Industrial School Cemetery, there is no signage directing people to this mass gravesite’s location on the riverbank behind Eiling Kramer campground.

In 2015, the Town of Battleford honoured a man named Lieutenant-Colonel William Otter by naming a major roadway after him - a road many First Nations people living on-reserve must drive in order to access the Battlefords from Highways 40 and 4. Otter was the Canadian military officer who towed a pair of Gatling guns to Cut Knife Hill in 1885 to attack Chief Pîhtokahanapiwiyin (Poundmaker) and his people during a period of unrest in the area. Indigenous scholarship has provided a much greater understanding of this so-called “battle”: the conflict had much more to do with growing frustration resulting in the 1885 resistance, in combination with factors like starvation, a rapid influx of settlers into the region, poverty, and harsh treatment of Indigenous people by local Indian Agents. By historical accounts, Otter came to make an aggressive show of force; he ultimately withdrew from battle, retreating in shame. Chief Poundmaker, known as a great peacemaker, stopped his people from attacking the retreating colonial soldiers.

Finally, the nearby Hamlet of Delmas is named after a Roman Catholic priest, Father Henri Delmas. Delmas was sent to the Thunderchild mission northwest of Battleford near the modern-day site of Delmas, before Chief Thunderchild and his people were forcibly relocated further north to their present reserve. Henri Delmas established the St. Henri / Thunderchild Residential School on his homestead in 1901. The school remained open until it burned in 1948. Father Delmas later became principal of St. Michael’s Residential School in Duck Lake - incidentally, one of the last residential schools to close in Saskatchewan in 1996. There is still an unmarked residential school cemetery on the grounds of Henri Delmas’ homestead near the Battlefords which local Indigenous and community groups are working to properly commemorate.

These are only a few examples of places that our community can look at to make change. We are all responsible for working to understand and learn about this history, and to act where we are able. The children buried at Kamloops Indian Residential School are a difficult reminder of what remains in our community’s own backyard. We must keep working together to acknowledge, understand, and begin charting a new path forward.

Benedict Feist

North Battleford

The National Residential School Crisis Line is available for Survivors and those who need it: 1-866-925-4419

Ěý