TORONTO — A coroner's inquest into the death of a mentally ill man at an Ontario jail heard Monday it was government policy that anyone whose health-care needs couldn't be met within an institution be sent to a community hospital or other outside health-care facility for treatment.

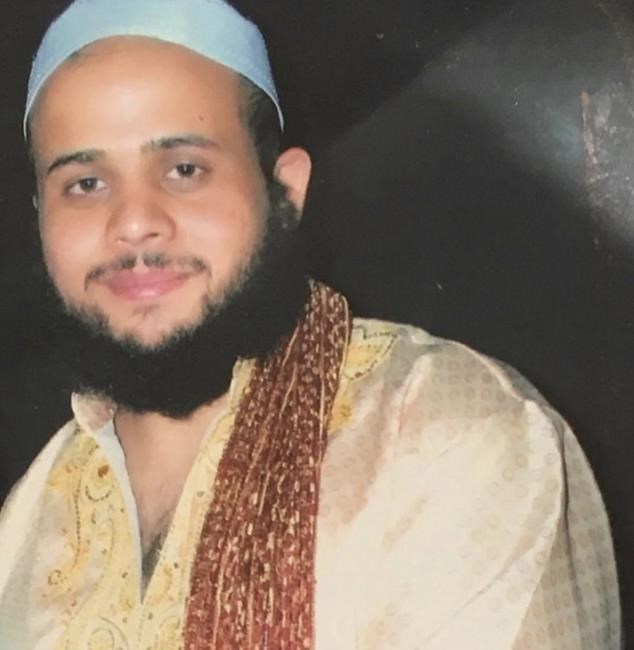

The inquest into the December 2016 death of Soleiman Faqiri heard from two senior officials with the Ministry of the Solicitor General, though neither had direct oversight of the case at the time.

Linda Ogilvie, who worked at the ministry's corporate health-care unit and reviewed Faqiri's file as part of an internal investigation, said it was the "expectation" even before December 2016 that institutions transfer people to community care if their health-care needs couldn't be met on site.

Those decisions are left to staff at the facility, a process that "does rely on the practitioners to certainly recognize that that care exceeds their ability," she said.

In reviewing his file, it's clear Faqiri was "very unwell," and it would have been expected to send him to hospital, she said.

The inquest has heard Faqiri was arrested in early December 2016 after allegedly stabbing a neighbour while experiencing a mental-health crisis.

Health-care and correctional staff at the Central East Correctional Centre in Lindsay, Ont., noted increasingly concerning behaviours over time, and one witness, a forensic psychiatrist, told the inquest Faqiri looked as though he was in the middle of a "very severe psychotic episode."Â

Faqiri died after a violent struggle with corrections officers on Dec. 15, 2016.

Ogilvie told the inquest her team did not have direct oversight over the jail but could provide support and act as consultants if an institution reached out. She said that did not happen during Faqiri's time in custody.

The ministry launched an internal review in November 2017 but front-line health-care workers weren't spoken to as part of the process, jurors heard. Ogilvie agreed it took too long for the review to begin.

"There may have been lessons learned, life-saving lessons learned, that were not noticed by the ministry for 11 months after Mr. Faqiri's death?" coroner's counsel Julian Roy asked her.

"Fair," she replied.

Roy asked Ogilvie if the review, or any additional steps taken following that, had shed light on why Faqiri wasn't sent to hospital, as would have been expected.

Ogilvie said she had only "anecdotal information" based on conversations with management at the jail.

"My understanding is that when patients were sent to the local hospital, they were often turned back at the emergency department and not provided a pathway for admission," she said.Â

In light of those experiences, staff may have thought "it would not be advantageous to send him out to that hospital at that time," particularly since other steps were being taken to try to get Faqiri care, she said.

Jurors have also heard Faqiri saw a physician but did not see a psychiatrist during his time in custody. Ogilvie said the institution's psychiatrist was on vacation at the time and while it would have been his responsibility to find someone to fill in, that could often prove difficult.

"In many cases, people will reach out to corporate health care and we will try to find somebody to help cover that individual so that they can go on vacation," she said.

"The other potential would have been using telemedicine and telepsychiatry," but those have limitations as not all patients can be seen that way, she said. Patients who are too ill for this avenue should be seen in person, she said.

The inquest has heard Faqiri was scheduled to undergo an assessment of his fitness to stand trial by video, but was deemed too unwell that day.

The inquest also heard from Tracey Gunton, another senior official with the ministry, who said the jail's relationship with the hospital is now "significantly better." Â Terms of service have been agreed on, though Gunton said she did not know if they had been signed.Â

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Nov. 27, 2023.

Paola Loriggio, The Canadian Press